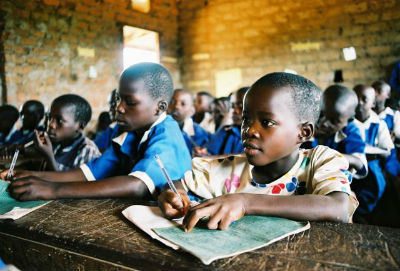

African Languages in Education

07/03/2014How important is it for older African children to be taught in their own language?

According to Laurinda Luffman, most people agree that educating nursery and primary school children in their mother tongue gives the best school results. She wonders, however, if this is also true for older children on the African continent. In an article on SOS Children, she shares the results of her research.

Luffman states that recently, the Zambian government has implemented a new education programme in which state schools are obliged to use the mother tongue of their primary school pupils as the language of education. Even though some schools find it difficult to realize the new rule, mainly because there aren’t any teaching materials in the local languages, Luffman believes the new measure is a big step for Zambia’s government. African countries were already encouraged to use children’s mother tongue in school by the UNESCO in 1953, so it is great that Zambia is finally taking actions.

Many studies have revealed that teaching children in their mother tongue positively influences the quality of learning and their educational achievements. Because of this, Luffman says, more and more African countries adopt the practice.

In a survey that was held by UNESCO in 2004, it was revealed that 70 to 75 per cent of all African children in nursery and primary schools were taught in an African language. Luffman does point out that only 176 of the 1000 existing languages on the continent were to be found in classrooms, however. In terms of basic education, the survey showed that only a quarter of all students was taught in African languages. This number was even lower in higher education, in which only 5 per cent was taught in local languages.

A lot of African governments, and many African parents as well, believe older children should be taught in the country’s official language, even more so if that language is recognised internationally. Luffman gives the example of Rwanda, where pupils in grade 1 to 4 are taught in Kinyarwanda, but are educated in English in the higher grades. This has affected the quality of the education: as English replaced French as the official language in 2008, Luffman says, there is a shortage teachers who speak the language and English language materials.

Even though Rwandan pupils are taught in English, only 4 per cent of them speaks English at home, Luffman says. These pupils mainly live in the big cities of the country, while nearly everyone in rural regions still uses Kinyarwanda at home. These children have great difficulties with taking their exams in grade 6 in the English language, Luffman states. Moreover, she says that a number of education experts believes using English as the language of instruction discriminates against the rural societies in Rwanda.

UNESCO agrees with these experts. In 2010, the organisation issued a study called “Why and how Africa should invest in African languages and multilingual education” which advocates the use of mother tongues in secondary and higher education [download the study here]. This is important as children understand difficult subjects such as science and maths better when they are taught in their own language. Moreover, teachers are more capable of explaining complicated matters in their mother tongue. If they have to use another language as their means of instruction, Luffman says, they need additional training in that language.

According to Luffman, Unesco also believes that pupils need more than three or four years to obtain a good grasp of a second language. She refers to a study that showed that year 5 students that were educated in the English language after being taught in Setswana for the first four years only knew around 800 English words, while 7,000 words are needed to understand the curriculum in year 5. Another study revealed that especially girls are slower when they have to answer in another language that their mother tongue as they are afraid they will be laughed at.

Luffman believes the proof that using the pupils’ mother tongue as the language of instruction is beyond doubt. However, she does admit that it will take some time before African governments and parents will also become aware of this fact. Until then, she says, it is very likely that many pupils that would have passed their exams with ease when they would have taken them in their own tongue will fail their exams now that they are still held in English.